- Home

- John David Smith

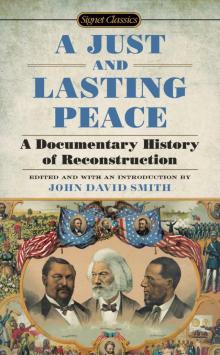

A Just and Lasting Peace: A Documentary History of Reconstruction

A Just and Lasting Peace: A Documentary History of Reconstruction Read online

A JUST AND LASTING PEACE

In 1862, as Union and Confederate soldiers continued to wage war, plans for the future of the country had already begun, set down in competing proclamations, essays and manifestos. After the South’s surrender, throughout the harrowing and chaotic process of Reconstruction, Americans voiced their hopes and grievances in private diaries and from public pulpits; brought court cases and launched bold new experiments in governance; hatched vicious plots to undermine order. It remains the most controversial and least understood period in American history. Through a selection of primary documents, A Just and Lasting Peace portrays the full scope of attitudes and conflicts that drove, threatened, and eventually won the modern union.

John David Smith is the Charles H. Stone Distinguished Professor of American History at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. He has been a fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies and received the Myers Center Award for the Study of Human Rights in North America. He currently serves as contributing editor for the Journal of American History and on the editorial boards of several scholarly journals. Among the books he has authored or edited are Black Voices from Reconstruction; Slavery, Race and American History; and Black Judas: William Hannibal Thomas and “The American Negro,” which won the Mayflower Society Award for Nonfiction. He has appeared on the History Channel, as an authority on the U.S. Colored Troops, and on Voice of America, as an authority on conservative racial thought during the Age of Jim Crow.

A

JUST AND

LASTING PEACE

A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF RECONSTRUCTION

EDITED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

JOHN DAVID SMITH

SIGNET CLASSICS

SIGNET CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

Penguin Books Ltd., Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com.

Published by Signet Classics, an imprint of New American Library,

a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright © John David Smith, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA

ISBN 978-1-101-61746-5

To Peter Coveney—friend and editor extraordinaire

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to acknowledge the support and research assistance of several persons who helped me in various ways in preparing A Just and Lasting Peace: David Blight, Ann Davis, Mary Dougherty, James J. Harris, Kathleen Johnson, Jane Knetzger, Charles McShane, Leigh Robbins, Sylvia A. Smith, Lois Stickell, Stephen Wrinn, and Andrew Zimmerman. Tracy Bernstein kindly asked me to undertake this project. Through the years, I have enjoyed working with a number of people at Penguin, including Charleen Davis, Michael Millman, Stephanie Smith, and Naomi Weinstein.

Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgments

Chronology of Reconstruction

Introduction

PART I

“AN ACT FOR THE RELEASE OF CERTAIN PERSONS HELD TO SERVICE OR LABOR IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA”

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, “PRELIMINARY EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION”

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, “EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION”

“PROCLAMATION OF AMNESTY AND RECONSTRUCTION”

THE WADE-DAVIS BILL

LINCOLN’S RESPONSE TO THE WADE-DAVIS BILL

THE WADE-DAVIS MANIFESTO

HENRY HIGHLAND GARNET, “LET THE MONSTER PERISH”

“AN ACT TO ESTABLISH A BUREAU FOR THE RELIEF OF FREEDMEN AND REFUGEES”

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, “SECOND INAUGURAL ADDRESS”

PART II

CHARLES SUMNER, “RIGHT AND DUTY OF COLORED FELLOW-CITIZENS IN THE ORGANIZATION OF GOVERNMENT”

ANDREW JOHNSON, “PROCLAMATION ESTABLISHING GOVERNMENT FOR NORTH CAROLINA”

ANDREW JOHNSON, “AMNESTY PROCLAMATION”

EMILY WATERS TO HER HUSBAND

THADDEUS STEVENS, “RECONSTRUCTION”

“A FREEDMEN’S BUREAU OFFICER REPORTS ON CONDITIONS IN MISSISSIPPI”

“FROM EDISTO ISLAND FREEDMEN TO ANDREW JOHNSON”

ANDREW JOHNSON, “MESSAGE TO CONGRESS”

AMENDMENT 13

“REPORT OF CARL SCHURZ ON THE STATES OF SOUTH CAROLINA, GEORGIA, ALABAMA, MISSISSIPPI, AND LOUISIANA”

LAWS OF THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI

JOSEPH S. FULLERTON TO ANDREW JOHNSON

JOHN RICHARD DENNETT, “VICKSBURG, MISS.”

PART III

CHARLES SUMNER TO THE DUCHESS OF ARGYLL

THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1866

BENJAMIN C. TRUMAN, “RELATIVE TO THE CONDITION OF THE SOUTHERN PEOPLE AND THE STATES IN WHICH THE REBELLION EXISTED”

CARL SCHURZ, “THE LOGICAL RESULTS OF THE WAR”

STATEMENT OF RHODA ANN CHILDS

GEORGE FITZHUGH, “CAMP LEE AND THE FREEDMAN’S [SIC] BUREAU”

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, “RECONSTRUCTION”

“PRESIDENT JOHNSON’S MESSAGE”

EXCERPTS FROM CLAUDE AUGUST CROMMELIN, A YOUNG DUTCHMAN VIEWS POST–CIVIL WAR AMERICA

HENRY LATHAM, BLACK AND WHITE: A JOURNAL OF A THREE MONTHS’ TOUR IN THE UNITED STATES

“AN ACT TO PROVIDE FOR MORE EFFICIENT GOVERNMENT OF THE REBEL STATES”

EDITORIAL IN THE CHARLOTTESVILLE CHRONICLE ON RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION

“THE PROSPECT OF RECONSTRUCTION”

“IMPEACHMENT FROM A LEGAL POINT OF VIEW”

“CONGRESS AND THE CONSTITUTION”

“THE PROSPECT AT THE SOUTH”

“LAND FOR THE LANDLESS”

THE RECONSTRUCTION ACT: PRO AND CON

“THE FREEDMEN”

THADDEUS STEVENS, “RECONSTRUCTION”

“THE NEGRO’S CLAIM TO OFFICE”

“SAMSON AGONISTES AT WASHINGTON”

GEORGE FITZHUGH, “CUI BONO?—THE NEGRO VOTE”

“THE VIRGINIA ELECTION”

“WHAT SHALL WE DO WITH THE INDIANS?”

ANDREW JOHNSON, “THIRD ANNUAL MESSAGE”

J. T. TROWBRIDGE, A PICTURE OF THE DESOLATED STATES; AND THE WORK OF RESTORATION, 1865–1868 (1868)

CORNELIA HANCOCK TO PHILADELPHIA FRIENDS ASSOCIATION FOR THE AID AND ELEVATION OF THE FREEDMEN

FRANCIS L. CARDOZO, “BREAK UP THE PLANTATION SYSTEM”

“THE IMPEACHMENT,” NEW YORK TIMES

S. A. ATKINSON, “THE SUPREME HOUR HAS COME”

“KARINUS,” LETTER TO THE EDITOR—“EQUAL SUFFRAGE IN MICHIGAN”

“THIS LITTLE BOY WOULD PERSIST IN HANDLING BOOKS ABOVE HIS CAPACITY”

THADDEUS STEVENS, “SPEECH ON IMPEACHMENT TRIAL OF ANDREW JOHNSON”

“THE RESULT OF THE TRIAL”

REPUBLICAN NATIONAL PLATFORM OF 1868

CAREY STYLES, “NOT OUR ‘BROTHER’ ”

AMENDMENT 14

HENRY

MCNEAL TURNER, “I CLAIM THE RIGHTS OF A MAN”

“REMARKS OF WILLIAM E. MAT[T]HEWS”

ULYSSES S. GRANT, “INAUGURAL ADDRESS”

LYDIA MARIA CHILD, “HOMESTEADS”

AMENDMENT 15

FREDERICK DOUGLASS, “AT LAST, AT LAST, THE BLACK MAN HAS A FUTURE”

CARL SCHURZ, “ENFORCEMENT OF THE FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT”

“AN ACT TO ENFORCE THE RIGHT OF CITIZENS OF THE UNITED STATES TO VOTE IN THE SEVERAL STATES OF THIS UNION, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES”

PROCEEDINGS OF THE KU KLUX TRIALS AT COLUMBIA, S.C., IN THE UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT, NOVEMBER TERM, 1871

HIRAM R. REVELS, “ABOLISH SEPARATE SCHOOLS”

ROBERT BROWN ELLIOTT, “THE AMNESTY BILL”

“AN ACT TO ENFORCE THE PROVISIONS OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES”

PART IV

CHARLES STEARNS, THE BLACK MAN OF THE SOUTH, AND THE REBELS; OR, THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FORMER, AND THE RECENT OUTRAGES OF THE LATTER

THOMAS NAST, “THE MAN WITH THE (CARPET) BAGS”

JAMES S. PIKE, THE PROSTRATE STATE

ROBERT BROWN ELLIOTT, “THE CIVIL RIGHTS BILL”

JOHN MERCER LANGSTON, “EQUALITY BEFORE THE LAW”

JAMES T. RAPIER, “CIVIL RIGHTS”

“AN ACT TO PROTECT ALL CITIZENS IN THEIR CIVIL AND LEGAL RIGHTS”

“THE NEGRO SPIRIT”

CARL SCHURZ, “HAYES VERSUS TILDEN”

THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON, “SOME WAR SCENES REVISITED”

D. H. CHAMBERLAIN, “RECONSTRUCTION AND THE NEGRO”

THE CIVIL RIGHTS CASES AND JUSTICE HARLAN’S DISSENT

WASHINGTON LAFAYETTE CLAYTON, OLDEN TIMES REVISITED

EXTRACTS FROM LAY MY BURDEN DOWN: A FOLK HISTORY OF SLAVERY

Sources of the Texts

Endnotes

CHRONOLOGY OF RECONSTRUCTION

April 16, 1862 Slaves in the District of Columbia emancipated.

September 22, 1862 Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation issued.

January 1, 1863 Final Emancipation Proclamation issued.

December 8, 1863 Lincoln issued Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction and announced the Ten Percent Plan of Reconstruction.

July 2, 1864 Wade-Davis Reconstruction Bill passed. First Freedmen’s Bureau Bill passed.

July 8, 1864 Lincoln issued pocket-veto proclamation on Wade-Davis Bill.

August 5, 1864 Wade-Davis Manifesto issued.

January 31, 1865 Thirteenth Amendment passed by Congress.

March 3, 1865 Freedmen’s Bureau established. Freedman’s Savings Bank incorporated.

April 14, 1865 Lincoln assassinated.

April 15, 1865 Johnson succeeded to the presidency.

May 9, 1865 Johnson recognized Pierpont government in Virginia.

May 10, 1865 Jefferson Davis captured at Irwinsville, Georgia.

May 29, 1865 Johnson issued Proclamation of Amnesty and inaugurated Presidential Reconstruction in North Carolina.

July to December 1865 Former Confederate states (except Texas) reorganized under Johnson’s plan.

December 4, 1865 Congress reconvened and refused to admit Southern members-elect.

December 6, 1865 Thirteenth Amendment ratified.

December 13, 1865 Congress established Joint Committee on Reconstruction.

February 19, 1866 Freedmen’s Bureau Bill vetoed by Johnson.

April 9, 1866 Civil Rights Bill passed over Johnson’s veto.

May 1866 Ku Klux Klan organized.

May 1–3, 1866 Memphis Race Riot.

June 13, 1866 Fourteenth Amendment passed by Congress.

June 20, 1866 Joint Committee on Reconstruction recommended that the former Rebel states were not entitled to representation and should remain under Congressional authority.

July 16, 1866 The second Freedmen’s Bureau Bill passed over Johnson’s veto.

July 24, 1866 Tennessee’s representatives readmitted to Congress.

July 30, 1866 New Orleans Race Riot.

August 28 to

September 15, 1866 Johnson’s “swing around the circle.”

January 7, 1867 Johnson’s impeachment proposed in Congress.

January 8, 1867 Black suffrage granted in District of Columbia.

January 25, 1867 Black suffrage extended to the territories.

March 2, 1867 First Reconstruction, Tenure of Office, and Army Appropriation Acts passed (first two over Johnson’s veto).

March 23, 1867 Second Reconstruction Act passed over Johnson’s veto.

July 19, 1867 Third Reconstruction Act passed over Johnson’s veto.

August 12, 1867 Johnson suspended Stanton and appointed Grant secretary of war.

October to

November 1867 Democratic victories in various Northern states.

December 7, 1867 Resolution for impeachment of Johnson failed.

January 13, 1868 Stanton restored to office by Senate.

February 21, 1868 Covode Resolution impeachment resolution made against Johnson.

February 24, 1868 Johnson impeached.

March 11, 1868 Fourth Reconstruction Act passed.

May 16, 1868 Johnson acquitted.

June 22–25, 1868 Arkansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Alabama, and Louisiana readmitted to the Union.

July 6, 1868 Freedmen’s Bureau continued by Congress.

July 9, 1868 Fourteenth Amendment ratified.

November 3, 1868 Grant elected president.

February 26, 1869 Fifteenth Amendment passed by Congress.

January 26, 1870 Virginia readmitted to the Union.

February 3, 1870 Fifteenth Amendment ratified.

February 23, 1870 Mississippi readmitted to the Union.

March 30, 1870 Texas readmitted to the Union.

May 31, 1870 First Enforcement Act enacted.

July 15, 1870 Georgia permanently readmitted to the Union.

February 28, 1871 Second Enforcement Act enacted.

March 3, 1871 Civil Service Law enacted.

April 20, 1871 Third Enforcement Act (Ku Klux Klan Act) passed by Congress.

May 22, 1872 General Amnesty Act passed.

November 5, 1872 Grant reelected.

September 18, 1873 Panic of 1873 began.

March 1, 1875 Civil Rights Act passed.

November 7, 1876 Disputed presidential election.

December 1876 to

March 1877 Congressional deadlock leading to Compromise of 1877.

January 29, 1877 Electoral Commission established.

March 2, 1877 Hayes declared victor over Tilden.

March 5, 1877 Hayes inaugurated.

April 3, 1877 Federal troops withdrawn from South Carolina statehouse and abandonment of state Republican administration.

April 20, 1877 Federal troops withdrawn from Louisiana statehouse and abandonment of state Republican administration.

October 15, 1883 Civil Rights Cases decided.

May 18, 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decided.

INTRODUCTION

The bloody American Civil War ground to a halt in April 1865, abolishing chattel slavery, establishing the sanctity of free labor, and maintaining the integrity of the American union. Despite the internecine struggle that cost possibly as many as 750,000 lives, the nation had survived.1 As historian Eric Foner, the foremost authority on postwar Reconstruction, has explained, “The Civil War changed the nature of warfare, gave rise to an empowered nation-state, vindicated the idea of free labor and destroyed the modern world’s greatest slave society. Each of these outcomes laid the foundation for the country we live in today. But as with all great historical events,

each outcome carried with it ambiguous, even contradictory, consequences.”2

In his Second Inaugural Address, delivered March 4, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln looked ahead to the reunification of the Union. He urged Americans, north and south, “to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.”3 Lincoln, whose life would be cut down by a Southern sympathizer on April 14, just five days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, had hoped to restore the Southern states to the Union smoothly and expeditiously. Months before his assassination the president had taken steps to ensure the constitutionality of the Emancipation Proclamation by supporting the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment (ultimately ratified on December 6, 1865). In his last public address, Lincoln referred to his 1863 “plan of re-construction (as the phrase goes)” and supported conferring the vote “on the very intelligent” African-American men, “and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.”4

War-weary Americans, however, soon learned that their much sought-after peace led to a bewildering array of constitutional, economic, and social problems. White Southerners, for example, struggled under the new order of things: life in a world without mastery over slaves. Though many feared retribution by their formerly “loyal” slaves, in fact most of the freedpeople sought to find loved ones separated by slavery, stabilize their families, find jobs either as laborers for wages or on “shares” of the crop, and create lives for themselves and their children. A former plantation mistress recorded in her diary late in 1865 her surprise at the behavior of the ex-slaves. “They are orderly & subordinate but incorrigibly lazy. Occasional acts of insubordination by the returned negro soldiers occurs here & there, but in this neighborhood we are exempt from all the ills of Emancipation save those which spring from Laziness & Theft.”5

Modern historians increasingly expand the traditional beginning and ending dates of Reconstruction. “If we come to regard emancipation as a protracted national process,” writes Steven Hahn, “we must also take a new look at the dimensions of what we call Reconstruction. Either Reconstruction must be seen as a similarly extended phenomenon, initiated in the Northern states well before the Southern (and thus almost coincidental with American nation building more generally), or we have to acknowledge a great many ‘rehearsals’ for the large-scale Reconstruction of the Civil War era: rehearsals that suggest different and more wide-ranging political dynamics (involving class, ethnicity, gender, and culture as much as race) than we are accustomed to recognizing.”6

A Just and Lasting Peace: A Documentary History of Reconstruction

A Just and Lasting Peace: A Documentary History of Reconstruction